Measuring the Cosmos

Last updated 9/14/2023 at 10:29am

Friedrich Wilhelm Bessel invented a way to measure the distance of stars that you probably learned about in elementary school. That's how he estimated the distance of star 61 Cygni.

My regular readers have surely become accustomed to seeing some pretty big numbers.

For example, in any one article, I might explain that our Milky Way galaxy is home to hundreds of billions of stars, that our sun produces 400 million billion megawatts of power each second or that the distances to even the nearest stars are measured in trillions of miles.

With each increasing number, I can imagine my readers' eyes rolling farther back into their heads. And that's understandable; other than astronomers, the only people who throw around such incomprehensibly large numbers are politicians!

Now I know that stargazers don't often vocalize it, but I'm sure everyone is wondering the same thing: "How can you possibly know that?" A natural question and, in the case of cosmic distances, the answer – at least in principle – is surprisingly simple.

Astronomers use one technique we all learned in elementary school and one we use to navigate our everyday world. It's called parallax, and you can demonstrate it like this.

Close one eye, hold out your thumb at arm's length and align it with a very distant object. Without moving your thumb, open your eye while closing the other. Notice how your thumb seems to have shifted relative to the more distant background object without ever moving it? Now bring your thumb closer to your eyes and try again. What happens now?

This apparent shift you see against the background is a measure of your thumb's parallax, and it's determined by the separation of your eyes (the "baseline") and their distance to your thumb. Since stars are considerably more distant, astronomers must use telescopes with more sophisticated equipment and much longer baselines.

The first ever to do this successfully was Friedrich Wilhelm Bessel (1784-1846), who used a telescope at the Konigsberg Observatory in East Prussia to measure the position of the faint star 61 Cygni relative to the more distant background stars. Six months later – when the Earth was on the opposite side of its orbit around the sun – he made the same measurement.

And in 1838, he proudly announced that his observations of the star showed a tiny parallax of a mere 0.314 arcseconds – the width a U.S. dime would appear if held at a distance of more than two and a half miles!

What Bessel achieved was stunning. Not only did he determine this star's parallax, but from it he calculated the star's distance. With this long baseline of 186 million miles, Bessel determined that the star 61 Cygni must lie about 61 trillion miles from Earth – pretty darned close to the 67 trillion miles we measure with modern equipment.

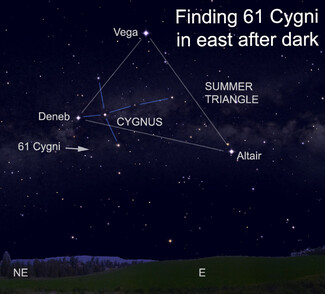

On the next really dark night, head outdoors to look high in the eastern sky for the three bright stars outlining the famous "Summer Triangle." There you'll spot the bright star Deneb, which is the tail star of Cygnus, the swan – also known as the Northern Cross – and just behind the swan's easternmost wing, the faint star we call 61 Cygni. Though it looks like most others, it was the study of this star 185 years ago that made it possible for humans to begin measuring the cosmos.

Visit Dennis Mammana at dennismammana.com.